-

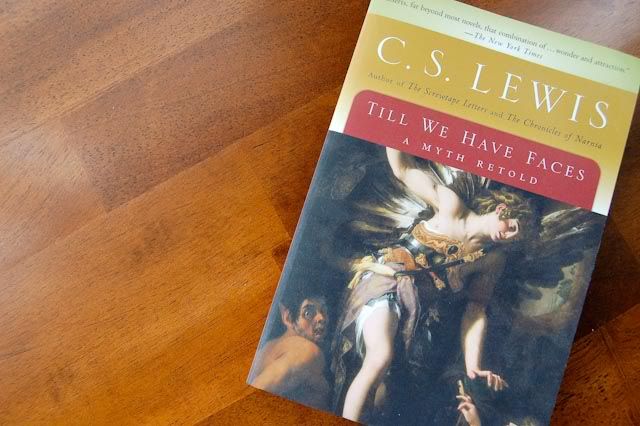

Along with my resolution to read a book a week in 2010, I hoped to find the time to write a few thoughts about each book on here as I finished them. And while I am (almost) on track with the reading aspect, I fell a bit behind these first few weeks in writing about the books. So, a bit belatedly, here are some thoughts on Till We Have Faces: A Myth Retold by C.S. Lewis, which I read the first week of the new year.

Also, I want to mention that I did originally write this for a class, so please excuse my authoritative tone. I honestly have not read any literary criticism on Lewis's book, so my understanding of the novel might not always be accurate. This is simply how I interpreted the book.

-Along with my resolution to read a book a week in 2010, I hoped to find the time to write a few thoughts about each book on here as I finished them. And while I am (almost) on track with the reading aspect, I fell a bit behind these first few weeks in writing about the books. So, a bit belatedly, here are some thoughts on Till We Have Faces: A Myth Retold by C.S. Lewis, which I read the first week of the new year.

Also, I want to mention that I did originally write this for a class, so please excuse my authoritative tone. I honestly have not read any literary criticism on Lewis's book, so my understanding of the novel might not always be accurate. This is simply how I interpreted the book.

I have heard from several sources that C.S. Lewis claimed that Till We Have Faces was his own favorite book of all that he had written. So it was with anticipation that I first opened the novel. Immediately, though, I noticed this book was unlike any of his other books. It still held the themes that will always be associated with Lewis--longing and desire and the nature of love--and it contained symbolism, like so many other of his novels, and yet it was heavier, deeper, more grotesque, if you will. But even amidst its depth, or perhaps because of it, I found the novel enchanting.

-

The book is a retelling of the Greek myth of Cupid and Psyche. Lewis altered the myth slightly to fit his purposes: he set the events in a different time period and place (a fictional, pre-Christian country near Hellenistic Greece), he added a few characters, and he developed his own theme. But for the most part, the novel is faithful to the original myth. The story tells of the ugly Orual who possessively loves her younger sister, Psyche. It is written in the first person from the perspective of Orual. Book one is her "accusation of the gods," in which she claims the gods have stolen Psyche's love from her. In book two, however, Orual reflects on her previous writing and tells how she has changed and how she believes what she wrote in the first half of the novel is all wrong--that it was herself, not the gods, who were to blame. The novel ends mid-sentence, and there is an after note that says Orual collapsed and died as she wrote.

-

As in many other of his novels, Lewis uses much symbolism. It is the case here also, though perhaps not so obvious. However, I want to write about two symbols, mainly because they illuminated to me the theme of the novel.

-

At the beginning of the book, the traits of a Christ figure become immediately apparent in the character of Psyche. She is described as supremely beautiful and innocent. She has miraculous powers and people flock to her so that they may be healed by her touch. And eventually, when the land of Glome has been scourged by disease, war, and lions, the people sacrifice her to the gods as she is the only one who is an image of perfection and worthy to be sacrificed in their place. She is hung on a bare tree and left to die. Her perfection, miraculous powers, and sacrificial death clearly mirror a Christ-life.

-

At the same time, however, she also is a symbol of a mortal seeking after truth. The name "Psyche" means "soul." Lewis himself said, speaking of Psyche, "She is in some ways like Christ because every good man or woman is like Christ." He clearly doesn't state that she is only a symbol of Christ, she is merely like Christ--and in her character, one can also see the elements of the human soul. For even amidst her perfection and beauty, she longs for "home," saying:

-

"The sweetest thing in all my life has been the longing--to reach the Mountain, to find the place where all the beauty came from...my country, the place where I ought to have been born. Do you think it all meant nothing, all the longing? The longing for home? For indeed it now feels not like going, but like going back. All my life the god of the Mountain has been wooing me. Oh, look up once at least before the end and wish me joy. I am going to my lover. Do you see now--?" (76)

-

This longing for home--or as Lewis believed, heaven--is something he believed characterized every human soul. In one of his more famous quotes, he says, "If I find in myself desires nothing in this world can satisfy, the only logical explanation is that I was made for another world." Accentuating his oft-used theme, Psyche's longing for "the place where all the beauty came from" clearly symbolizes her as a mortal and reminds us of our own longings for another world.

-

Another striking symbol in the novel is the veil that Psyche's sister, Orual, wears in the latter half of the book. Orual constantly speaks of her own ugliness and the veil is her way of covering up her unattractiveness. But there seems to be a deeper meaning to the veil. One of the main themes of the novel, as expressed in the title, is that we cannot understand the intent of the gods--or God--until we see them ourselves. At the end of the book, Orual says:

-

"I saw well why the gods do not speak to us openly, nor let us answer. Till that word can be dug out of us, why should they hear the babble we think we mean? How can they meet us face to face till we have faces?" (294)

-

The veil, therefore, is a symbol of our own veiled faces--of how humanity cannot fully see, cannot fully understand. Of how we are blinded to the supernatural world that invisibly walks among us. At the very end of the novel, when Orual finally sees the gods and the world and herself for what they really are, Orual writes, "Hands came from behind me and tore off my veil--after it, every rag I had on" (289). In the presence of the gods, her veil is torn from her and her vision is restored. She sees, understands, comprehends.

-

I also found, besides the symbolism, that the first-person point of view furthered the themes of the novel. In the first part of the book, as we see through Orual's eyes, we feel partial to her--we too feel angry with the gods for screwing up her life when she seems so innocent. While perhaps here and there we might question her actions or accusations, for the most part the reader feels the same hatred that Orual feels at the end of book one.

-

In book two, Orual still speaks in the first person, but in a more humble, reflective way. Looking back on the tale that she told in book one, she perceives herself how possessive her love was towards others, how it was she who so often birthed the problems she faced. Through the first person, we too see how self-favoring and one-sided our understanding of the world so often is. We enter into Orual's journey and become like her, in a sense, traveling with her through anger and hardening and ultimately into a sort of shocked and humble repentance in the presence of the gods.

-

It was these things--the symbolism and the perspective--that to me made the book deeper and more thought-provoking. But the story itself was captivating, the type of book that you set down and cannot wait to pick it up again. My first week back to school was quite often interrupted with extra long lunch breaks! Lewis once again wrote a purely enjoyable novel.

-

And while this might sound contradictory, I think one of the most surprising elements to me in Till We Have Faces is how little specific Christian symbolism Lewis used. I've highlighted the main ones--and really, Psyche's sacrificial death is the only obvious one. A reader could certainly enjoy the book without knowing anything of Lewis's background. And I think is one of the main reasons the book appeals to me. It is not so straightforward. It is graver, more intense, even more confusing than his other novels. I opened up the first page and was daunted by the host of strange mythical names and the foreign, barbaric setting, but eventually, the novel wove itself into me--and now, two weeks after I finished it, I am still trying to wrap my mind around the themes and nature of the novel. It is the type of book that merits more than one reading.

-

And lastly, I think one could say that the book might be summed up in one of my favorite Bible passages, I Corinthians 13:12, "Now we see but a poor reflection as in a mirror; then we shall see face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I am fully known."

-

Book Information:

Published in 1956 by Harcourt Books

313 pages

Book One: 21 chapters | Book Two: 4 chapters

Note from C.S. Lewis at the end outlining the original myth of Cupid and Psyche

Price: $10.08

-

No comments:

Post a Comment